World War II: A Tale of 2 Sisters

This is my dad H.W. Davis’ 5th in a series of guest posts about the experiences of our family members during The Great Depression and World War II. This post is about my grandmother (my dad’s mother-in-law) and her sister. They were too young to serve during the war, but they had their own unique experiences during World War II. If you want to read more of my dad’s talented writing, download his 1st published book. Seeking Diana by H.W. Davis is available for Kindle by clicking here. Hope you enjoy these old war stories! -Stephen

READ MY 3 PREVIOUS POSTS ABOUT MY DAD’S EXPERIENCE SERVING WITH THE 1st MARINES IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II.

- World War II Memories From The South Pacific: Part I

- World War II Memories From The South Pacific: Part II – Borneo and New Guinea

- World War II Memories From The South Pacific: Part III – Okinawa

ALSO CLICK HERE TO READ MY 4TH POST IN THE SERIES, ABOUT MY MOTHER AND HER EXPERIENCE AS AN ARMY NURSE DURING WORLD WAR II.

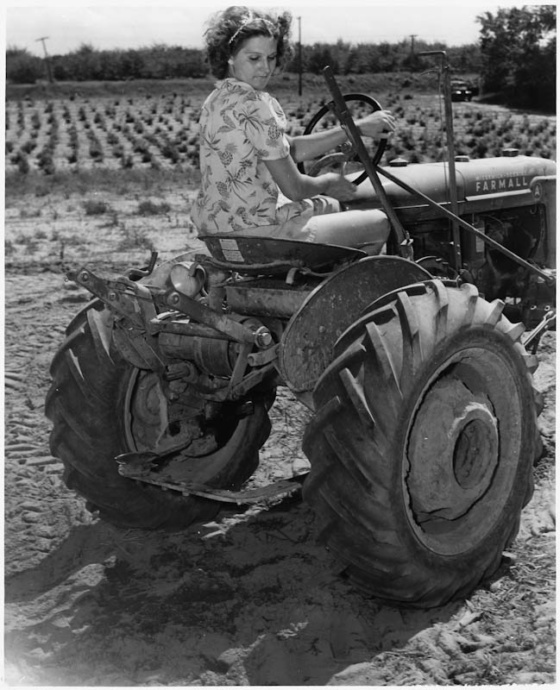

From the city to the farm, it was common for families to move to the country and grow their own food during The Great Depression.

WORLD WAR II: A TALE OF 2 SISTERS

When Pearl Harbor occurred, my wife’s mother, Corinne Standefer Smith was 9 years old, and her older sister, Mary Rose Standefer Pace was 13. Their father was a banker, and they already were familiar with the ravages of The Great Depression. They had spent nearly two years living on a farm in Marion, Arkansas before their father, Edwin Standefer could return to his job with a bank in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1940, Edwin bought a new house on Goodlett Road on the far eastern edge of Memphis. This location is noteworthy because Goodlett Road dead ends at the start of what was the Kennedy Veteran’s Hospital. The location also housed German and Italian prisoners of war.

BACK TO THE CITY

Mary Rose and Corinne recounted those days with a mixture of fondness and humor. Like most Americans, their consumer decisions were limited by the war. Because of gas and tire rationing, Edwin rode the bus downtown to his job at the bank. They recall collecting cans for the scrap metal drives. Cloth and shoes were rationed. Their mother, Jewel Standefer, was an excellent seamstress who sewed most of their clothes. Jewel came by material as best she could. Because butter and cooking fats were rationed for the war effort, oleo / margarine became more common. Mary Rose said it was white and resembled lard in appearance. That admittedly does not sound very appetizing! The oleo came with a packet of yellow food coloring which the purchaser could mix into the oleo if bothered by the unappetizing appearance. She laughingly said that they often just ate it white.

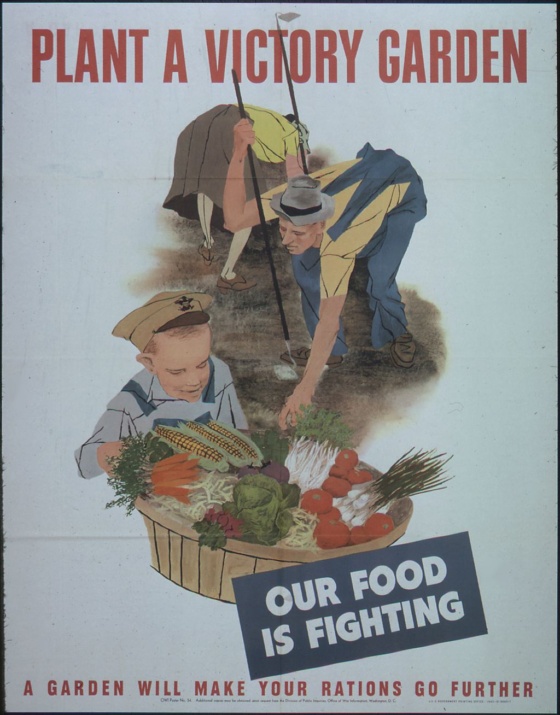

VICTORY GARDEN

In an effort to feed her family better, Jewel Standefer joined millions of other Americans in planting a Victory garden in their backyard. They grew tomatoes and numerous vegetables. Since eggs were rationed, Jewel decided that they would raise chickens for the eggs. They were on the edge of town, and wild animals were a concern as far as protecting their chickens. Therefore, she made a chicken coop in the attic. The oldest child Miles was responsible for feeding the chickens and cleaning up. The smell was not very good. Jewel and her daughters would collect the eggs. Many years later, my wife and I rented the Standefer home for a year. One Saturday out of curiosity I climbed the stairs into the attic. There, I found old newspapers from the war years placed on the floor and a bunch of chicken feathers.

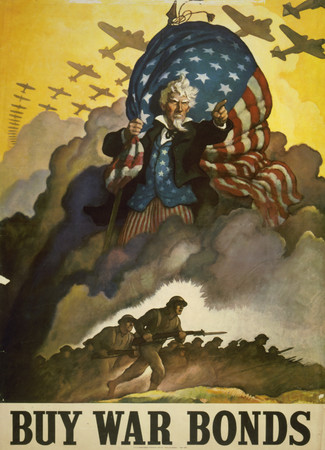

WAR BONDS

WAR BONDS

Mary Rose recently recounted the war bond drives that were so prevalent during the war years. The teachers at their elementary and junior high schools collected money from the students for bonds, perhaps 25 cents at a time. When a student’s account reached $10.00 he or she received a war bond. It was a source of pride for the children. They felt that they, too, were contributing to the war effort.

PRISONERS OF WAR ON THE STREETS OF MEMPHIS

Another memory from those years concerned the Kennedy Veteran’s Hospital. Wounded military personnel were constantly arriving and departing. There was a train depot at the time on Southern Avenue across from what is now The University of Memphis.. It was where the wounded arrived and the healed departed. Mary Rose remembers a steady stream of military trucks and ambulances going both directions. They went down Goodlett right past the Standefer home. She recounts that they and the older children would wave to them as they passed.

German and Italian prisoners of war were quartered near Kennedy Hospital. They were used for labor on streets and landscaping. Corinne recalled that the younger children were scared and ran inside whenever these pow’s passed by on Goodlett. However, Mary Rose has more humorous memories. Italian officers were quartered at Kennedy. The American guards would march them down Goodlett for exercise. She particularly enjoyed seeing the Italian officers. They would dress in their finery and march down the street with great pomp and ceremony. In contrast, many of the German pow’s were enlisted men, and they were put to work. Their American guards would supervise them as they performed street repairs or cutting grass with scissors. While I initially found it surprising that the Germans would be given scissors, most of them were very well behaved. They told reporters that they were grateful to be in Memphis were they received humane treatment and adequate food versus being stuck in some Soviet hell-hole in Siberia.

Language problems occasionally created some interesting situations. Mary Rose remembers one such incident with humor. Across the street from her home was a forest known as Goodlett Woods. An old man and his wife had a modest cottage at he edge of the woods, and he was paid to do maintenance work. In his front yard was a water spigot and a hose. One summer day the German pow’s were working hard near his house. It was a hot, humid Memphis summer day, and one of the pow’s indicated to a guard that he was very thirsty. The guard tried as best he could to tell the prisoner to get a drink of water from the water spigot. Apparently the pow misunderstood and wandered across Goodlett Road, which at the time was just a narrow two lane street. He entered the yard of the Standefer’s next door neighbor and started searching for water. He eventually went behind the house and entered the rear door into the kitchen. There, a young mother was feeding her infant who sat in a high chair. Initially Ann was frightened if not terrified by the unexpected appearance of this dirty, sweaty German pow. Fortunately, she kept her cool and the equally shocked German tried to convey his need. Once she understood that “wasser” was water, she gave him a glass. He smiled and gratefully drank it before wishing her an “auf weidersehen.” He then returned to his work crew across the street.

THE EFFECTS OF WAR

On a more somber note, Corinne and Mary Rose remembered those who didn’t come home or who came home damaged. Nearly every family had members who were serving in the military, many in harm’s way overseas. Many of their friends had fathers or older brothers in the service. They were a source of both great pride and worry. It became even more personal when their older brother Miles joined the Marines and served in the bloody Battle of Okinawa. Fortunately, Miles returned home.

After the war, Mary Rose Standefer married Bob Pace who spent the war mostly in Rio de Janeiro deciphering coded secret German messages which mostly came via Argentina. Corinne Standefer married my father-in-law, Cecil Smith, who served during the Korean War. All of them used the G.I. Bill to continue their educations and buy their first homes. Cecil and Corinne would start a successful insurance agency. Bob became a business man, and Mary Rose taught school. During an era of racial unrest, she volunteered to teach in an impoverished inner city school where she was very effective. Miles would earn a law degree and work as a bank trust officer. They all raised children and took pride that their kids would face an easier life than had they during The Greatest Generation.